Wax Print: Africa’s Pride Or Colonial Legacy?

- Home

- Wax Print: Africa’s Pride Or Colonial Legacy?

Wax Print: Africa’s Pride Or Colonial Legacy?

Fridays are the day to wear “African print” outfits in Ghanaian offices, yet some designers are boycotting such fabrics – arguing they are not actually African.

The history behind the designs is complex – and involves several continents.

Office workers Joseph Appiah-Dolphyne and Karen Dodoo are shocked to discover the provenance of the popular prints they wear.

The two business journalists at Adom News were decked out in similar outfits when I visited their office one Friday in the capital Accra – though hers was purple and his green.

The pair had not co-ordinated their wardrobes, yet weren’t surprised by the coincidence.

They told me that the circular design was called “subura” which means “water well” in English and is one of the most popular patterns in Ghana.

“When you go downtown on a Friday you meet a lot of people with the same pattern,” Mr Appiah-Dolphyne said.

He was right. Walking through Accra’s Makola market, it seemed as though every other person who walked past was wearing it – like baker Gloria Assagba, who had designed her own trouser suit.

The government’s campaign to get people into national dress on Fridays started in 2004 to support the local textile industry, yet a lot of the fabric worn is not made by African firms.

Ms Dodoo’s fabric, for example, was made by Chinese brand Hitarget.

She said she clubbed together with others to buy it: “We chose the Chinese fabric because 12 of us from church were all getting the same outfit and it was cheaper.”

Mr Appiah-Dolphyne bought his fabric from Ghana Textiles Printing (GTP), which, despite its name, is owned by Dutch company Vlisco – which also designed the print.

He was shocked when I told him that it was Dutchman Piet Snel who had created it in 1936 for Vlisco.

“It was designed in Europe? That’s news to me. I thought it was designed in Ghana. It’s sad to hear. We can easily design clothes, so why not do it?”

These sentiments are shared by Ghanaian designer Nana Kwame Adusei.

He refuses to use African wax prints, as they are known, for his ready-to-wear clothing brand Ćharlotte Prive, saying they are a legacy of colonialism.

“The wax print companies have been making money for 170 years and the money doesn’t come back to us.”

This has also put off Nigerian Amaka Osakwe from using them in her fashion label Maki Oh while Malian-born indigo dyer Aboubakar Fofana has said he could “never agree with the use of wax print to symbolise African-ness”.

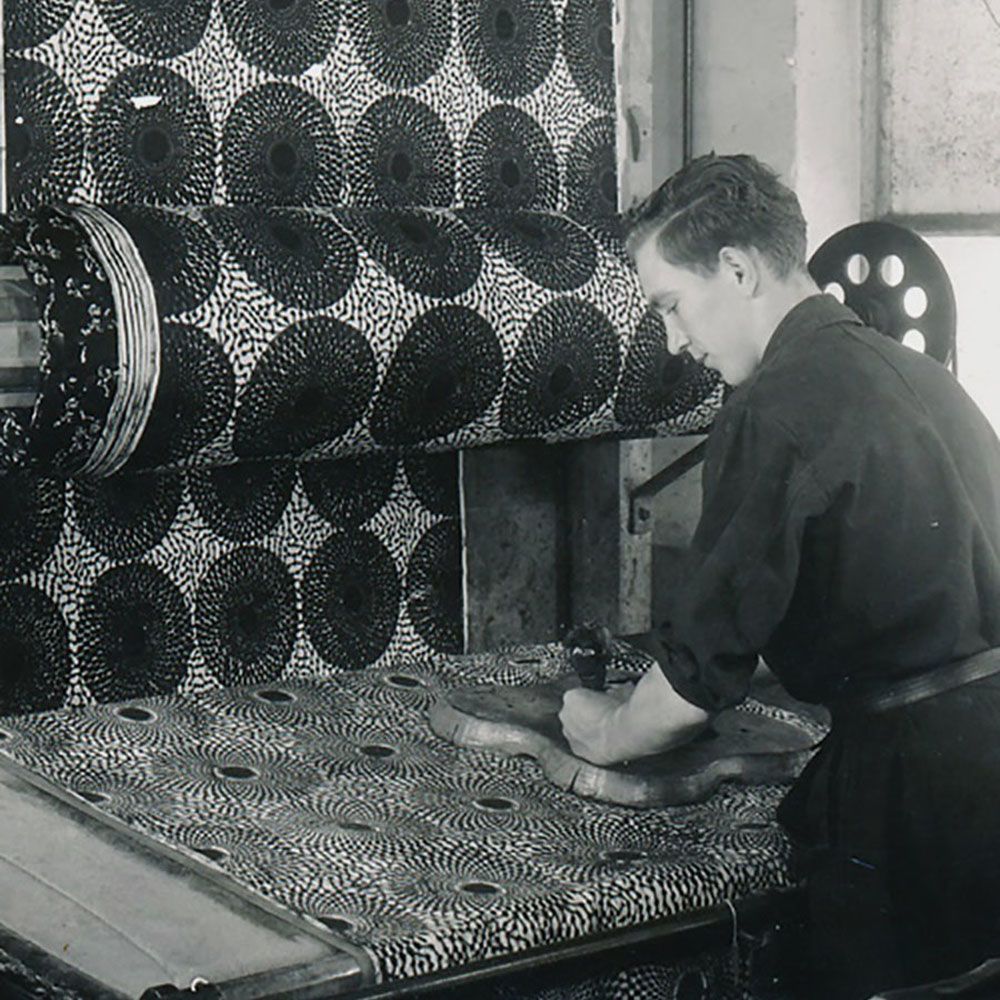

What these designers are touching on is the intriguing history of wax print dating back to the Napoleonic wars in what is now Indonesia – and the local, hand-made method of making batiks.

This laborious process was recorded in detail by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, governor of what was Java in 1811 when the British captured the island from the Dutch.

He explained how hot wax was passed through a tube to draw designs on to fabric which was dyed and then re-waxed and dyed again for up to 17 days.

“He then sent 22 pieces of Indonesian batik back to England with a challenge to the men of industry to find a way to mechanise it,” explains documentary maker Aiwan Obinyan, who traced the history of the print in the film Wax Print.

A peace treaty returned Java to the Netherlands and Raffles left. But the Dutch could also use his book to help work out how to mechanise the process so they could undercut expensive hand-made batiks.

And in the end the Dutch won the race against the British.

The first batch of machine-made batiks was exported from Holland to the Dutch East Indies in around 1850, writes anthropologist Anne Grosfilley in African Wax Print Textiles.

But it was a flop and the fabric sold at a loss.

Ms Grosfilley said this was in part because Javanese artisans had started applying wax with stamps, so cutting their costs, and making their cloth more affordable.

Nonetheless the Dutch continued exporting their wax prints to the region for the next 22 years – a period when they were expanding their colonies.

The Dutch had employed 3,000 soldiers from West Africa, between 1831 and 1872, to help in this expansion.

The African troops were used in particular in the fight against the rulers of Sumatra, writes historian Ineke van Kessel in an exhibition at the Elmina Java Museum.

Legend has it that 700 of these soldiers eventually returned to the Gold Coast, modern-day Ghana, carrying with them rolls of the Dutch-manufuactured batiks.

It is impossible to prove if this was indeed the case but Ms Grosfilley says that “it has become the way the European companies Vlisco and [UK-based firm] ABC like to talk about the beginning of wax print in West Africa”.

For Ms Van Kessel, it remains a myth as she says the returning soldiers were poor and would not have been able to afford the fabric.

What is known is that Swiss missionaries a few years later wrote to a Scottish trader to inform him that there was a growing demand for these wax prints in West Africa – because the material was easier for sewing machines to stitch than the thicker locally woven material.

“These industrial prints inspired by Javanese batiks were ideal: light material, but with an indigo base – they were exotic in a way, but also had some similarities with the West African traditional local tie-dye,” said Ms Grosfilley.

In 1893, more than 20 years after the batik exports to the Dutch East Indies had ended, Scottish businessman Ebenezer Brown Fleming delivered the first cargo of Dutch industrial batiks to the Gold Coast.

By 1907, Brown Fleming had started commissioning English printers to make wax print too.

The missionaries were thrilled as they were on a mission, literally, to teach women to sew and use these skills to earn an income – and promote a modest dress code at the same time.

That legacy still lives on – walking down an average street in a typical Accra neighbourhood there is a tailor every few shops.

Markets today even sell some of Brown Fleming’s very first patterns, including one design sometimes called “skin” or “house marbles”.

It was created for a Dutch firm and its patent, registered in 1895, has been found in the records at the UK’s National Archives at Kew by researcher Helen Elands.

Nearly 125 years later, the design was on the catwalk at the October 2019 Accra Fashion Week in Portia Kemi Attipoe’s beachwear collection under the Lapokela brand.

“It’s an old cloth, and it’s popular. Everyone has this,” she told me.

She remembered her grandmother wearing a blue-and-white version of it to christenings and naming ceremonies when she was growing up – and refused to accept that it was designed in Europe.

“This is definitely an African design,” she said.

She said that the pattern had a Ghanaian name and that, to her, proved its West African heritage.

She called it “efie aboseaa” which means “gravel” and explained that the pattern resembled the small stones people would keep outside their houses.

Vlisco, which now manufactures the design along with ABC, says that the paving stones are a metaphor about how one’s immediate family can give the most pain because “it’s sometimes sharp and can cut you deeply”.

“The poor don’t eat stones” was another interpretation I was given of the pattern, meaning that poor people still have to eat food just like everybody else.

The fabric acquired a new meaning when HIV started to spread in the 1990s, writes Ms Grosfilley.

The original design had “small motifs that resemble the letters V, I and H”, she explains.

“It caused controversy when the spread of HIV/Aids was at its height. Rumours quickly circulated that people wearing this design were carriers of the disease, and the drop in sales in Nigeria forced the English company ABC to slightly modify the design.”

This has now made it possible to spot counterfeits of the design imported from Asia as they have never modified the pattern, she says.

However, the counterfeiters did modify their prices – downward.

In a small alleyway in Accra’s busy Makola market I found Serwaa Darko selling fabric.

The shelves in her mother’s small shop were packed from floor to ceiling with a seemingly never-ending combination of colours and patterns, including “house marbles” by three different brands:

- The Dutch-made Vlisco cost 530 Ghanaian cedis ($63; £49) for six yards (about 5.5m)

- The GTP fabric – made in Ghana by a Dutch-owned firm – was 130 cedis

- Chinese brand Hitarget cost just 55 cedis

Another locally made brand, ATL (Akosombo Textiles Limited), was not available, as Ms Darko says she hasn’t been able to get hold of their fabrics for a while.

The competition is proving tough for the brand.

The firm was set up in 1967 by an entrepreneur from Hong Kong, Cha Chi Ming, and named after the place on Ghana’s Volta River where he set up a factory.

It did well for several decades, with one of its best sellers being the “house marbles” design which he had bought the rights for in 1992.

But by the end of 2017, the factory was struggling with debt, and when it looked as if it was about to close, the government stepped in to take over the company.

Yet on the day I visited, nothing was being made.

General Manager Ken Asare told me the factory had a capacity to print 28 million yards of fabric a year but in 2018 had only printed one million yards.

“The biggest challenge is the dumping of cheap products from the Far East. Their prices are lower than ours.”

He said the Asian cloth used to come in illegally, without paying duty – and while the government was clamping down on that, other challenges were making it difficult to compete.

On a recent trip to Pakistan he realised that manufacturers there had far lower tariffs for electricity – paying $0.05 to produce one yard of fabric compared to between $0.10 and $0.15 in Ghana.

Former workers told me they had given up hope and moved on to other jobs. Even my taxi driver in Akosombo had worked at the factory until earlier in 2019.

Yet almost by accident, when the government took over the factory they created an African-owned factory for African print – something US enthusiast Amma Aboagye has long dreamt about.

Born to Ghanaian parents, she started a firm called Afropole which tries to connect “African and Afro-diasporan” businesses around the world “so that we can build generational wealth”.

She started questioning the African-ness of wax prints in her teens at the African-Carribean shop run by her parents in Capitol Heights, Maryland in the US.

“I was in my parents’ store and fabric was being delivered by an Indian man, who imported his fabrics from India.

“The print had never actually touched the continent, as in it came directly from Asia to the United States of America into the store.”

This troubled her.

“People were connecting with the fabric as a representation of their identity, of their culture, of a place or heritage, however, it had no economic benefit to that place.”

As an adult she moved to Ghana and last June started the Wax Print Fest – a weekend gathering for fashionistas where they discussed whether the fabrics could really be considered as African.

Afterwards she came to the conclusion that their African-ness, despite their origin, could not be ignored.

“We recognise that wax print today is definitely a reflection of our own ideas, symbols, conversations, histories, many of the fabrics canonised important moments in our history as African countries,” she said.

Research by Ms Elands backs up this argument, and she gives one classic design – “staff of kingship” – as an example.

The pattern portrays a sword – now found in the British Museum, which the museum says was used for the inauguration of the Asante kings before it was “removed from the Asante by the British in 1900”.

Ms Elands says to protest about the sword’s theft, some people in what is now Ghana commissioned ABC Wax in England in the 1920s to create the design and make the cloth.

They exercised enough power to get a fabric made in the same country they were protesting about.

This, for her, shows the consumer is king – and the consumers of African prints are mostly African.

And as if proof was needed, I met Esther Mensah in an elegantly-tailored dress made out of “staff of kingship” fabric as she made her way to church one Sunday in Hohoe, not far from where the Asante kingdom once ruled.

Credits

Written and researched by Clare Spencer

Photography by Ben Bond, Clare Spencer and Phil Coomes

Archive pictures from DexTee Studios, The Trustees of the British Museum and Vlisco Archive

Produced by Phil Coomes

Edited by Lucy Fleming and Joseph Winter

Source: BBC

Classic Ghana

Classic Ghana brings you into a fun world of arts, entertainment, fashion, beauty, photography, culture and all things in between. Let’s explore these together!